Chapter 1: Education in colonial times

Chapter 2: Post-Revolution Education

Chapter 3: The Civil War and West Virginia Statehood

Chapter 4: Education System under the 1872 Constitution

Chapter 5: Era of Transformation, 1880-1909

Chapter 6 1909-1932: The Age of Uniformity & the Battle Between Old School and Progressive Education

Chapter 7 1933-1950: Education under the county unit, the Great Depression, WWII and Beyond

Chapter 2: Post-Revolution Education

One major shift which occurred after the Revolution was the shift of educational responsibilities from the Church to the government. The secularization of the responsibilities for educating indigent and orphaned children did not occur overnight, nor at one specific level of government. At local levels, duties were transferred from churchwardens to county justices. At the state level, the move to secularize government took several years. At Virginia’s state constitutional convention, James Madison tweaked George Mason’s call for religious toleration into the phrase “free exercise of religion,” which he would later include in the First Amendment to the US Constitution. Parish taxes, which had been used to teach indigent children as well as fund the state-sponsored church, were no longer collected during the Revolution. After the Revolution, it was proposed that the tax be reinstated, but there was an effusion of protest and petition against its reinstatement. The distaste for government-established religion had grown. In 1785, a bill to renew the tax was narrowly defeated. By 1786, Thomas Jefferson had issued his “Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom” further separating church and State. The General Assembly passed a law requiring all poor apprentices, regardless of sex, to be educated in reading and writing, omitting religious instruction which had been part of previous regulations concerning the education of poor and indigent children. This shift is evidence of the institutionalization of the separation of church and state and the obligation of the state to provide education to indigent and orphaned children.

But to be clear, the apprenticeship laws of the time, and over the next several decades, were first and foremost economically based and did not have the educational welfare of the children in mind as its primary goal. There was, however, an expanding belief in the necessity of an educated citizenry. Thomas Jefferson promoted the idea of educating, at the expense of the public, children whose families could not afford it . Although his proposal failed passage several times, his idea eventually gained traction.

Virginia Education System

The growing sentiment for an educated citizenry led to the 1796 law, “Act to Establish Public Schools,” which established an aldermanic system of schools. In this law, counties would be divided into districts. Each district would have their own schools, providing free primary education for all white children. Each county, via popular election, would appoint three aldermen who would thereby divide the county into districts, each given a name. The aldermen, meeting with property owners of each district, determined a location for a school. Once the schoolhouse was built, the alderman’s job was to select a teacher and oversee his effectiveness.

In this system, all white children were to receive a free education for three years with the option of their parents paying tuition afterwards. The school system would be funded by the residents of these districts “in proportion to the amount of their public assessments and county levies.” Like other taxes, the sheriff was to collect these school taxes and transfer receipts to the Alderman. At the time of its passage there were ten counties in existence which would become part of West Virginia-- “Hampshire, Berkeley, Monongalia, Ohio, Greenbrier, Harrison, Hardy, Randolph, Pendleton, and Kanawha, formed in the order named.” Ohio County contained the land which would become Wetzel County. This education law was ahead of its time in attempting free education for all white boys and girls. Because its scope was so large and its premises so new, it was not successful.

The aldermanic law was a failure due in part to lack of funding, but also because the timetable for the creation of local schools was entirely left up to the alderman of each locality. Additionally, the infrastructure for such a monumental bill was not in place to properly implement such a far reaching piece of legislation. Its failure led to the introduction of other bills which attempted to establish the infrastructure needed for a free school system. First of these, the “Act Concerning the Glebe Lands,” was introduced in 1802 and created a pathway for the introduction of a subsequent bill to fund a general education system. The state of Virginia contained lands that had previously been owned by the Anglican church. To dispose of these lands, this bill would use the sale of such Anglican properties to fund education, depositing them in a Literary Fund. Also, “escheats, penalties, and forfeitures” which had previously gone to the King were now to be invested in the fund as well, “appropriated to the encouragement of learning.”

The 1802 bill was referred to committees, but was lost in the legislative process until 1809 when it was finally reported, albeit in another form. This new bill would create a Literary Fund -- financed through the sale of glebe lands and other fines and forfeitures. The Literary Fund bill passed during the 1810 session. In 1811, the General Assembly passed “An Act to Provide for the Education of the Poor,” thereby creating the administrative offices necessary to collect, maintain, and administer the Literary Fund, though specifying more clearly the recipients of the funds, i.e. the poor. Additionally, the 1811 law created the Literary Board -- consisting of the governor, lieutenant governor, state treasurer, and the head justice of the state court of appeals. Together they were known as “the President and Directors of the Literary Fund.” It should be noted that no new positions were created to administer this new agency, but rather the duties of existing offices were simply extended.

Many Virginians were opposed to this new educational system. Some did not agree with publicly supported education of the poor, declaring it created a system of state-dependent paupers. Others contended it gave state government unwarranted control over local funds and educational jurisdiction. Thomas Jefferson was among the latter group, despite being a long time advocate for public education. He saw it as the beginning of a series of steps in which state government would usurp local control.

However, the county still retained local administrative powers, vesting authority in five to fifteen school commissioners who were appointed by local justices. Commissioners had the ability to determine: which children, and how many, would receive an education; where schools would be erected; and which teachers would be employed. The only restriction on their authority was they could not require compulsory attendance.

In 1818, another act passed by the General Assembly extended the allocation of funds to a proposed (by Jefferson) university. While the establishment of the Literary Fund in 1810 has been deemed as the bedrock for the public school systems in both Virginia and West Virginia, this new piece of legislation was also fundamental. The Literary Fund was an attempt to solve the illiteracy problem from the bottom up. This new legislation established funds for higher education in an attempt to solve it from the top down as well. When the system faced poorly trained and educated schoolmasters in the future, this precedent would be essential, leading the way to funding higher institutions of learning, as well as standardized training and certification of teachers.

The new education system under the Literary Fund was not without flaws. It was difficult to establish consistency among districts as to determining which students were deemed poor or indigent. Some counties failed to expend allocated funds, while others failed to appoint commissioners in the first place. But the system was generally considered to be a positive good, and worthy of augmentation, as opposed to dismantling. Therefore, several attempts were made to improve it.

Punitive measures were instituted in 1822 and 1823 for failure to implement the education system. Clerks could be fined for failing to report financials to the Literary Board. Commissioners were also susceptible to fines for failure to report as well. Justices could be fined for failure to fill commissioner positions. Allowances for fulfillment of duties were revoked from commissioners. Another act, in 1823, countered the negative ramifications of these first two laws. It created a second state auditor position -- specifically for the allocation of Literary Funds -- that would eventually evolve into the state superintendent of schools. Luckily, the man who filled the position, James Brown, Jr. was magnanimous and used his powers to positively improve the school system. Additionally, his long tenure (1823-1852) contributed a level of consistency of administration which the Literary Fund had not yet seen.

Superintendent Brown standardized reports required from county commissioners on the state of schools within their districts. These reports were used: to compile data on districts that had failed to implement the Literary Fund to create a schools system; to identify districts that had not allocated funds properly; and to identify districts which needed more funding. The reports additionally addressed: specific difficulties of determining who composed the indigent poor; of retaining competent teachers; and lack of funding for supplies. Commissioners often overspent their allotted allowances and some were ordered by law to reimburse funds.

Despite many obstacles, progress had been made, and Brown’s data collection showed it. Joseph Martin, in 1835, used this data in his “Gazetteer of Virginia” to show that within the twenty-four counties which would become West Virginia, in less than thirty years (with three counties not reporting) there were 678 primary schools attended by poor children.

At the time, the region which would become Wetzel County, was a part of Tyler County. The region which became Tyler county had been the most southern part of Ohio County, i.e. after Ohio had been partitioned from West Augusta in 1776. Tyler was partitioned from Ohio County by Act of Assembly in 1814. According to Joseph Martin, Tyler County had 11 school commissioners and twenty primary schools. His records indicate 216 of 450 poor children as being enrolled. The county spent an average, per diem, of two cents on each student. An average of $1.20 was spent on each child from the Literary Fund. Relative to other counties of western Virginia at the time, expenditures for students in Tyler county were on the low end. But it had lower levels of population in comparison to other counties, and with higher rates of poverty, allotted expenditures were rationed among more students.

Education Conventions

Higher rates of poverty and distressed funding were par for the course for western counties of Virginia. While progress was being made in western counties, a sentiment existed of being short shrifted compared to eastern Virginia. Wealth, population, and political power was concentrated in the east. For children in the east, the result was more educational opportunities . While westerners supported the expansion of public funding for all school-age children, easterners were unwilling to expand the Literary Fund, which would lead to increased taxes. But when the government released the results of the 1840 census, Virginians witnessed the results of an underfunded education system. Illiteracy rates had risen compared to other states, especially those in the free North, where they had fallen. The embarrassment of these results led to louder calls for educational reform, even in the east.

In response, over the next two decades, a series of educational conventions began to be held in various parts of the state pushing for reform. This push was promoted by Protestant leaders from western counties as well as those worried of rising illiteracy rates. While the General Assembly failed, again, to reform education, it did defer to the president and directors of the Literary Fund to submit a plan to better the school system. With a nod from the Literary Fund Board, conventions were organized.

On September 8-9, 1841, the first of these conventions was held in Clarksburg, Harrison County . It was the westernmost convention held and was led by area religious leaders. Its goal was to compel the General Assembly to create a free school system. Representatives from nineteen counties were present; sixteen of the nineteen counties are in present day West Virginia. Tyler County, of which Wetzel was still a part, was represented by ten delegates.

The discontent of the western counties regarding the inequities of the current education system was evident in the proceedings. Delegates’ desires for reform were summed up in the address made by Reverend Dr. Alexander Campbell. He proclaimed, “We do not want poor schools for poor scholars, or gratuitous instruction for paupers; but we want schools for all at the expense of all.” Delegates suggested financing a new school system through a common tax on property, along with the creation of a state superintendent similar to the role of Superintendent Brown though with more control over educational funding.

Several plans were proposed, each calling for a free district common school system. On the first day, the plan of John D. D. Rosset was read to the convention and tabled. His plan, the most radical of those proposed those two days, was described as being “one hundred years ahead of [its] time.” He advocated for abolishing the Literary Fund altogether, transferring those funds to the general council; using public land sales, increasing property taxes to 2.5 cents per $100 land value assessed; and raising levies 25 cents per person. He also proposed the establishment of a permanent pension fund for teachers. This would help combat transient and unqualified teachers. Another aspect of his plan was to limit the amount of funds allocated to universities.

For the western delegates at the Convention, the issue of funding universities through the Literary Fund was a major sticking point. . Henry Ruffner-- who also proposed a plan for a free district school system-- admonished the use of “eight hundred thousand dollars spent on the university,” stating it was equivalent to “put[ting] a fine curved and gilded top to a house, with a foundation of dirt, and walls of rough logs badly put together.” He called the funding of the university as it was-- the rich were educating their sons at public cost ($800,000), while the counties were only given $70,000 per year to teach just a fraction of the poor children in the state. The poor school system was underfunded. The teachers were untrained. The days attended were insufficient to teach the children, and the parents were “too ignorant and too careless to teach them at home.” While poor children were found throughout the state, there were higher concentrations in the western counties.

Ruffner’s plan for change was more tempered than Rosset’s. Rufner, too, believed in district schools, but retained the Literary Fund supplemented by property tax and parental tuition contributions. He proposed that districts be classed according to those “most able and populous” to support a school system. First class would have year round school; lesser classes would attend only three or four months, depending on availability and amount of funds. Property taxes, which would fund teacher salaries, would be a burden shared by all, not solely by parents of children. Taxes would be divided proportionally to the districts as their categorization determined need. Tuition would be paid, on a sliding scale, by those who could afford it. There would be state-level and county-level superintendents with district commissioners, assigned to determine school locations, construction, and maintenance of buildings. Also, Normal Schools would be established to train qualified teachers.

The convention agreed to form committees to release reports of the proceedings to both the the legislature and the citizens of the state of Virginia. Their purpose was to garner public support and persuade the legislature to reform the education system. In each of these reports, it was argued the necessity of having an informed, moral and educated public in a republican form of government. They underscored the worries of the recent census that had indicated the decline of literate Virginians. It was not solely in the best interest of the common good that its children receive an education, but a civic and moral duty of the state to provide one.

Mainly on the grounds of Ruffner’s plan, the memorial (for the legislature) laid out a plan for reforming the education system . The new law would create a district school system which would include the authority to levy a property tax to supplement the Literary Fund. There would be a state superintendent with other officers to help fulfill duties. Each county would have a superintendent. After the counties created districts, each district would elect three to five trustees who would supervise the construction and maintenance of schools, along with the hiring of teachers. If districts did not form school systems within three years, Literary Funds and property taxes thus collected would return to the general fund. The system would have tuition gratis. The schools would be effective-- “If they are not good enough for the rich they will not be fit for the poor,” --and taught by qualified teachers trained in proper schools. Finally the Literary Fund would be expanded to meet the financial needs of a free district school system.

Although not the last educational convention -- and it did not lead to immediate legislative action --it has been considered, “[t]he most important education meeting ever held on the soil of West Virginia, before or since…” This convention agitated more people than ever before to advocate for free schools . Western Virginians were particularly interested and followed conventions held later that year in Lexington and Richmond.

The Lexington Convention, held on October 7, 1841, endorsed Ruffner’s plan, not a free school system. It greatly criticized the indigent “pauper dole” and believed the current system needed reformed, though not a complete renovation, as endorsed by the Clarksburg Memorial. On the other hand, the Richmond Education Convention did endorse a free education system, funded by taxes. However, it also emphasized the need to fund universities at public expense as well. Again, differences between the eastern and western counties, and the divisions between the richer and poorer counties, all resurfaced.

Even though all of these conventions forwarded their convention memorials to the legislature, it would be several years before the general assembly took up the issue of education reform. On March 5, 1846 two acts were passed to reform the present schools system, but neither established free schools. Together, through elections authorized by school commissioners, they established the creation of county superintendents and limited the duties and influence of commissioners. The new superintendent position was created to circumvent the corruption which seemed rampant among school commissioners. Superintendents were to take over the treasury responsibilities of fund allocations, teacher pay, etc., as well as make report on educational progress within the county. Their salaries were based upon the 2.5% of total expenditures from the previous year. This system gave incentive for superintendents to encourage commissioners (who still retained this power) to identify more indigent students who might qualify for literary funds, thus expanding the poor school system.

Despite western Virginia’s preference for the new system, it failed to be an improvement over the previous one. The average attendance of poor children dropped by twelve days and the per student tuition contribution decreased by nearly forty cents per student. Allotted county budgets continued to go unspent, but this was because the law required counties to distribute the funds equally among the districts. Some districts did not have the population to sustain a school system. But western counties generally agreed the schools were overall beneficial, even if it was not a free school system as they so desired.

Wetzel Becomes a Separate County

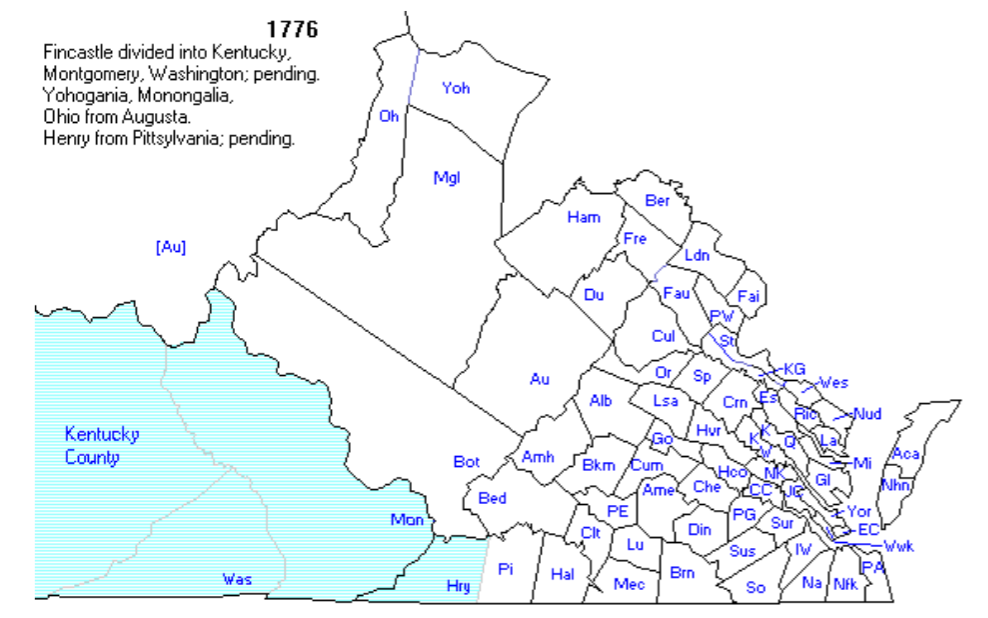

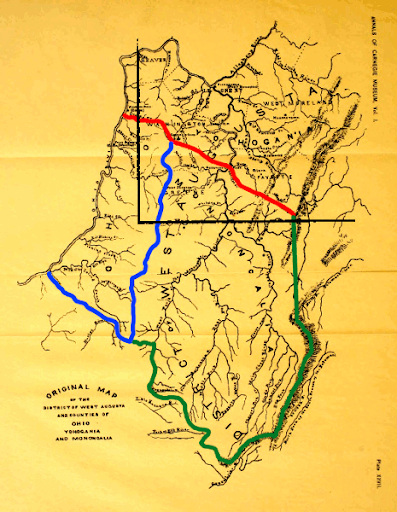

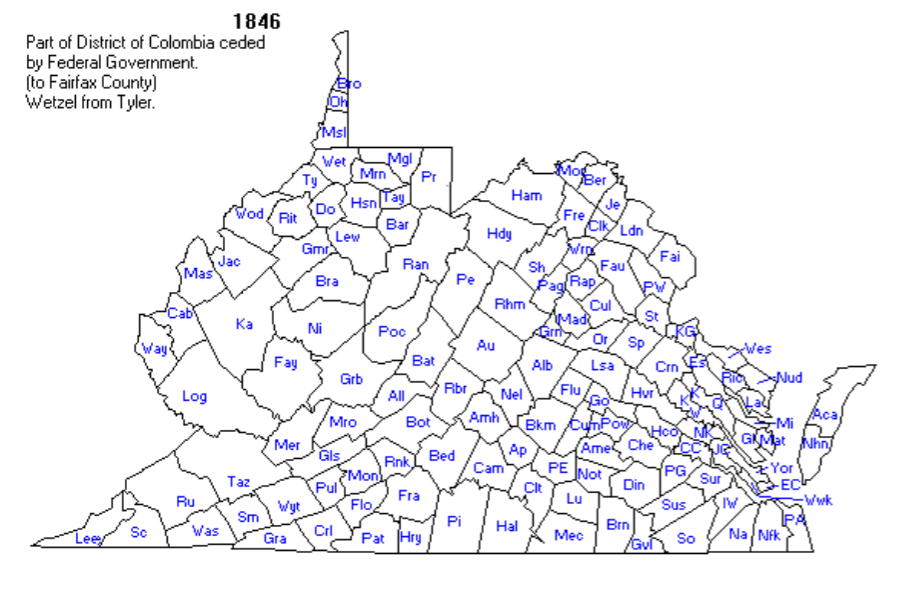

At this point it is necessary to shift topics from education over to the study of the creation of Wetzel County. It was previously mentioned that Wetzel county was originally part of the territory of West Augusta. In November of 1776, West Augusta was broken into three separate districts, Youghiogheny, Ohio and Monongalia. Together, these three encompass much of what is today considered northern and north central West Virginia,as well as parts of south-western Pennsylvania. The boundary between Virginia and Pennsylvania was disputed until October 8, 1785 when the western boundary of PA was established five degrees west longitude from the Delaware River. In 1767, the southern border of PA had been established by two English engineers, Mason and Dixon. During the 1785 legislative debate, this narrow passage of land separating Pennsylvania from the Ohio River Valley became known as the ‘Panhandle’ . All of the territory of the panhandle, as well as some additional land south of the Mason Dixon line became part of Ohio County -- a total of 935.85 square miles. In 1814, Tyler county broke away from Ohio by an act of Virginia Assembly. All land south of the Mason Dixon intersection was now designated ‘Tyler County’, the northern tract of which would eventually become Wetzel County.

This area was sparsely populated at the time. The first attempt of settlement in what would become the county seat of Wetzel occurred in 1780 by Edward Doolin who had secured 800 acres along the Ohio River near the mouth of Fishing Creek. He was murdered by Indians four years later. Further settlement into the area trickled in slowly from the Ohio River as well as from the east. By the 1780s and 1790s, people had begun settling into what would become the interior (i.e. away from the Ohio River) districts of Wetzel-- Church, Green, and Grant. Church district was settled by Henry Church in 1782; James Troy settled Green in 1791; and in 1790, Grant was settled by John Wyatt , and six years later, by William Ice, Henry Talkington and Aiden Bales. By the early 1800s, Center was settled by Benjamin Bond (1805) and Clay was settled by William Little. Due to the precipitous geographic terrain, much of the area remained untamed and growth was slow. From the time of these first settlements until 1838, the population grew slowly. It would not be until nearly mid 19th century that the population had amassed enough numbers to constitute application for separate countyhood. On January 10, 1846, Wetzel County, pared from the northern section of Tyler county, was created by an act of the Virginia Legislature . It received its name from Louis (sometimes spelled Lewis) Wetzel, a famed “frontiersman” and Indian fighter who was rumored to have scalped approximately one hundred Natives.

By the time Wetzel County had become its own political entity, the education system -- under the Literary Fund -- of the state of Virginia was in its thirty-sixth year of existence. While the general sentiment of the populous was critical of this system, the inertia of the status quo made it difficult to restructure education in the state. Two more educational conventions were held prior to the outbreak of the Civil War, one in 1856 and another the following year. These conventions, and the committee reports produced by them, recognized the inadequacies of the Literary Fund system. But no changes were made. And as before, criticism from western counties and calls for universal primary education continued. In places where district free schools had been established due to concentrated populations (i.e. Kanawha, Jefferson and Ohio), surpluses intended for isolated districts with little population were redirected to the city schools. While this may have been considered a misuse of funds in the east, it was necessary for the nature of settlement in the west. In those places where schools could be established, more students had access to an education, and not simply indigent children.

This trend of sentiment is telling for what will come during the Civil War years. Francis H. Pierpont, often referred to as the Father of West Virginia, Governor of the Restored State of Virginia during the Civil War and the early part of Reconstruction, was the superintendent of schools for Marion county, neighbor to Wetzel. He believed “the state owes a primary education to all its children,” --i.e. a free public school system-- and championed for a continuation of the literary fund supplemented by inheritance and corporate taxes. His influence in the formation of the West Virginia Constitution would ensure that free public education would become a constitutional right for all children of West Virginia.

Bibliography

“A Bill for the More General Diffusion of Knowledge, 18 June 1779” Founders Online National Archives. https://founders.archives.gov/?q=Act%20to%20Establish%20Public%20Schools&s=1511311112&r=2 .

Ambler, Charles H. A History of Education in West Virginia: From Early Colonial Times to 1949. Huntington: Standard Printing & Publishing Company. 1951.

Berkes, Anna. “A Bill for the More General Diffusion of Knowledge.” Thomas Jefferson Foundation. 2009. https://www.monticello.org/site/research-and-collections/bill-more-general-diffusion-knowledge#footnote2_wb4i3fb .

Hennen, Ray V. West Virginia Geological Survey- Marshall, Wetzel and Tyler Counties.(Charleston: The Acme Publishing Company. 1909. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=inu.30000080353570;view=1up;seq=28

Martin, Joseph. A New and Comprehensive Gazetteer of Virginia, and the District of Columbia: Containing a Copious Collection of Geographical, Statistical, Political, Commercial, Religious, Moral and Miscellaneous Information, Collected and Compiled from the Most Respectable, and Chiefly from Original Sources. Charlottesville: Moseley & Tompkins, Printers. 1835.

Matzko, Paul, Ph.D., “Virginia’s Religious Disestablishment.” Association of Religion Data Archives. http://www.thearda.com/timeline/events/event_13.asp

McEldowney John C., Jr. History of Wetzel County, West Virginia. 1901.

Miller, Thomas C. “The History of Education in West Virginia,” Charleston: Tribune Printing Company, 1907.

Andrea Null, “Wetzel County.” e-WV: The West Virginia Encyclopedia. 04 June 2013. Web. 21 March 2019. https://www.wvencyclopedia.org/articles/1158

“History of Wetzel County” published by John Null 1900.

Rice, Otis K. and Stephen W. Brown. West Virginia: A History. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky.1993.

Ruffner, Henry. “Outlines of a Plan for the Improvement of Common Schools in Virginia: Prepared at the Request of the Kanawha Lyceum.” Journal of the House of Delegates of Virginia Session 1841-1842. Exchange Duplicate, LC. Richmond: Samuel Shepherd, Printer of the Commonwealth, 1841.

Rutherfoord, ed. “Address of the Education Convention.” Journal of the House of Delegates of Virginia Session 1841-1842. Exchange Duplicate, LC. Richmond: Samuel Shepherd, Printer of the Commonwealth, 1841.

Rutherfoord, John, ed. “Education Convention of Northwestern Virginia.” Journal of the House of Delegates of Virginia Session 1841-1842. Exchange Duplicate, LC. Richmond: Samuel Shepherd, Printer of the Commonwealth, 1841.

Rutherfoord, ed. “Memorial of the Education Convention” Journal of the House of Delegates of Virginia Session 1841-1842. Exchange Duplicate, LC. Richmond: Samuel Shepherd, Printer of the Commonwealth, 1841.

Rutherfoord, ed. Rosset, John D. D. “Project, Based for a Law Upon the Public Education in Virginia.” Journal of the House of Delegates of Virginia Session 1841-1842. Exchange Duplicate, LC. Richmond: Samuel Shepherd, Printer of the Commonwealth, 1841.

Sullivan, Debra K. “Education” E-WV: The West Virginia Encyclopedia. 2013. https://www.wvencyclopedia.org/articles/2163 .

West Virginia Heritage, Volume Two. West Virginia Heritage Foundation. Richwood, WV. 1968.

Whitehill, AR, “History of Education in West Virginia,” United States Bureau of Education Circular of Information No. 1, 1902. Washington: Government Printing Office.