Chapter 1: Education in colonial times

Chapter 2: Post-Revolution Education

Chapter 3: The Civil War and West Virginia Statehood

Chapter 4: Education System under the 1872 Constitution

Chapter 5: Era of Transformation, 1880-1909

Chapter 6 1909-1932: The Age of Uniformity & the Battle Between Old School and Progressive Education

Chapter 7 1933-1950: Education under the county unit, the Great Depression, WWII and Beyond

Chapter 3: The Civil War and West Virginia Statehood

Differences between eastern and western Virginia were prevalent, the divergent stances regarding universal education being just one of many. Most importantly, much of the landscape of the western section of the state was not conducive to the type of agriculture which was dependent upon slave labor at the time. Because of this, there were few slaves in the western region -- less than 4% -- and strong sentiment of free labor dominated much of the residents in the area. In 1851, Daniel Webster spoke to this growing division centered on slavery.

And ye men of Western Virginia who occupy the slope from the Alleghenies to the Ohio and Kentucky, what benefit do you propose to yourself by disunion? If you secede what do you secede from and what do you secede to? Do you look for the current of the Ohio to change and bring you and your commerce to the waters of Eastern rivers? What man can supposed that you would remain a part and parcel of Virginia a month after Virginia had ceased to be part and parcel of the United States?

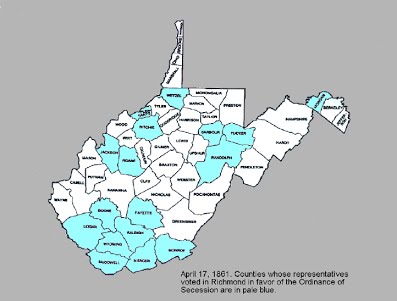

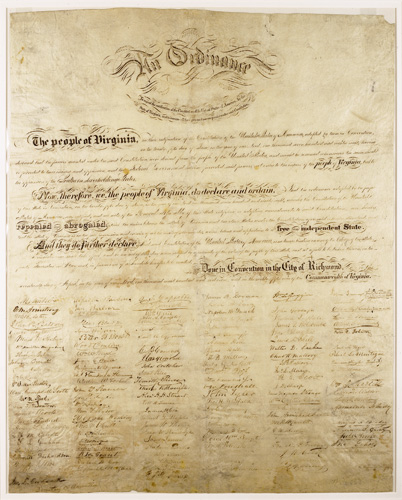

This was an ominous prediction by one of the greatest statesmen who spent his career trying to amend the separation between North and South and who understood clearly the economic differences between these two regions. A decade later, Webster’s predictions had come true and people in western Virginia had to choose their loyalty. After southern states began to secede, Governor Letcher of Virginia called a special session of the assembly to discuss the state’s next step. The assembly met January 7, 1861 to authorize a special election for delegates to a convention that would determine secession. Western counties meeting on the matter vehemently protested a convention. Despite protest, it met February 14, 1861 and stayed in session until May 1. During this time an ordinance of secession was passed (April 17), although western delegates voted against it nearly 3 to 1.

After the Richmond secession meeting ended, meetings were conducted throughout the western counties calling for a separate meeting. Led by John S. Carlile, an anti-secessionist delegate present at the Richmond Convention, a movement began for a convention to be held in Wheeling . For this first meeting at Washington Hall in Wheeling, more than 400 delegates arrived . Several decisions were made. First, the convention agreed to break away from Virginia and form a new state. This created a dilemma -- the more conservative delegates opposed immediate rash decisions. Francis H. Pierpont advanced an idea: this first convention should call for a new convention, one which localities would elect delegates, and subsequently members of a second convention could choose a method and plan for separation. This would give time for cooler heads to prevail as well as legitimize any actions taken by the second convention since it had been approved by the electorate.

The second Wheeling Convention began on June 11 and two plans were presented to the representatives. First, the convention could promptly form a new state from western counties who were loyal to the Union. Secondly, the convention could reorganize the western counties under a restored Virginia government. The advantages of the second plan-- Virginia was an already recognized state in the Union-- gained favor because it seemed the least possibly resisted plan by the federal government. Also, a state could only be “legally dismembered” by its own consent, paving a way for future statehood under its own pretenses. This second planned passed by a unanimous vote. Soon, the formation of a interim government was underway and on August 20 an ordinance was passed to form a new state constitution and create a new form of government. This was presented to the people via referendum on October 24--18,408 for, 781 against-- and elected delegates to a constitutional convention, one where the new constitution would be written.

1863 Constitution and the beginning of Free Schools

The first constitution created a system of free public schools, a right that was constitutionally protected. This came as no surprise as it had been the western counties who had advocated for decades to create a free school system. Reverend Gordon Battelle and Reverend Alexander Martin, both part of the “Northern” Methodist movement, were leading advocates of the free system. Though both were educated in the north and exposed to education systems in Ohio and Pennsylvania, the educational system they created was influenced by the Virginia system. Martin’s “An Outline of a System of General Education for the New State” contained many of the elements of the Virginia system, but corrected its deficits. All primary schools would be free. They would be funded by a state property tax, a permanent literary fund, as well as local taxes. Like the Virginia system, there would be local officers and county superintendents. A general superintendent would entail the same duties of Virginia’s second auditor. Also, there would be a state board of education, somewhat like the Literary Fund Board.

The Committee on Education planned to fund the schools by using accrued interest from stock owned by the State in bank or corporations, plus any sales of said stocks to a vested school fund. Also, they wanted personal property and corporate (a bonus tax) taxes to fund the schools. While there were no delegates who were against a free school system, there were some who were against the means proposed to fund it. Conservatives disagreed with using stock dividends or sales because that money was to be allotted to pay the state’s bonded debt.

They opposed taxation on corporations for two reasons. First, they believed the bonus tax was double taxation and secondly, they believed it would deter capital investment in the state. The progressives counter-argued, affirming the new system could designate bond dividends and sales for any purpose they wanted, and further argued the need for an educated body politic.

Their argument was not strong enough. Proceeds from stocks would go to public. The school fund would receive money from

the sale of forfeited delinquent, waste, and unappropriated lands, of lands forfeited to the state for the non-payment of taxes, of grants, devises, and bequests made to the state; to the state’s share in the Virginia Literary Fund or in moneys, stocks, and property owned by her for educational purposes; to estates escheating to the state and accruing to her in the case of persons dying without wills or heirs; to military exemption funds; and to such sums as the legislature appropriated from time to time.

The viability of the financial future was restricted by these limitations leaving the future of its success on the legislature’s willingness to pass laws authorizing state taxes and local levies. Additionally, conservatives were against a vested school fund, wanting all funds collected annually to be spent annually. This would leave no rainy day insurance for years of economic recession and expose to bankruptcy the free school system during economic downturns.

Fortunately, many of the financing details would be left to legislative action. But a victory had been won for public education. The new constitution stated:

The Legislature shall provide, as soon as practicable, for the establishment of a thorough and efficient system of free schools. They shall provide for the support of such schools by appropriating therto the interest of the invested school fund; the net proceeds of all forfeitures, confiscations and fines accruing to this State under the laws thereof; and by general taxation on persons and property , or otherwise. They shall also provide for raising, in each township, by the authority of the people thereof, such a proportion of the amount required for the support of free schools therein as shall be prescribed by general laws.

The new constitution, including its article guaranteeing free education, was submitted to the people on March 26, 1863. On April 20, 1863, President Lincoln proclaimed West Virginia would be admitted to the Union on June 20, 1863.

The first legislature passed the first education law on December 10, 1863. It mandated a six month school term. Each county would be divided into townships; each township had administrative control over its school system. Voters in the townships would elect three commissioners annually. They would oversee employment of teachers and determine their salary and student curriculum. Commissioners were also in charge of building and maintaining schools, calculating levy payments, and making payments to contracted employees. Each county had a superintendent who would be elected to a two year term. He was responsible for teacher examination and certification, overseeing schools throughout the county, coordinating professional development textbook adoption, and report directly to the general superintendent of the condition of schools within his county.

Establishment of first schools and development of teachers (1865-1880s)

This school system, as innovative as it was for the newly formed state, proved to have several problems not unlike the old Virginia system. There were three main categories of issues: funding, ignorance and/or corruption at the local level, and the need for qualified teachers.

Funding

The most essential issue determining the success or failure of the new system was its ability to be funded. The first legislature did not adequately fund the schools’ system so the second (1864) legislature attempted to fix the problem. Many localities were unable to guarantee six months of education because township levies had not met the required local contributions, creating a school system with “great inequalities.” The legislature believed that the burden of finance should be shifted to the state. Local levy contributions would be reduced if state school tax was increased. However, conservatives defeated the measure. Again, in 1865 and 1866 statutory changes were made to try to increase the amount of money local townships could raise. Yet the changes proved inadequate to raise the necessary funds. By 1867, the solution to the problem was decided-- reduce the required term to four months rather than six. Until Radicals were voted out in the 1870s, the state school tax was ten cents per $100 valuation and local levies could be up to fifty cents per $100 valuation for school buildings, and another fifty cents for teachers (one dollar together), ultimately however the township electorate saw fit.

Local corruption

Another problem facing local schools systems was the “misapplication of school funds.” This was due to several factors. First, the new system lacked any system of oversight.. Local officials were “neglect[ful]” or “malfeasan[t]” of their duties. County superintendents reported levy money to have been “squandered by the board.” Officers supplemented their allotted salaries with funds designated for schools and teachers. In 1866, the legislature tried to fix this through the creation of elected trustee positions for each subdistrict, thereby removing monetary decisions from commissioners. However, in 1867 the township boards were bestowed the authority to appoint the trustees, thus creating a system susceptible to nepotism. Superintendent White believed that a solution to the problem would be to remove local township control and give authority to county boards, streamlining the chain of command for more direct oversight from his office.

Teachers

The first General Superintendent, Ryland White (June 1, 1864- March 3, 1869) wanted to bring uniformity to the teaching profession. He called for the establishment of teacher training schools, i.e. Normal Schools. He said, “It would be better to suspend the schools of the State for two years and donate the entire school revenues for that time to the establishment and endowment of a State Normal School than to have none at all.” In short, he felt opening primary schools without properly trained teachers was like putting the cart before the horse. His efforts were not in vain. In 1867, the legislature authorized the funding of three Normal Schools-- Fairmont, West Liberty, and Marshall. Five years later three more were established-- Shepherdstown, Glenville, and Concord.

When the first education laws were passed, there was no certification or examination process required for teachers. After much avocation by White, the legislature authorized the first certification process in 1866. On recommendation from county superintendents, certificates were issued by the general superintendent . Another act in 1867 created five categories of certification and separated primary from high school certifications.

However, the legislature during this time period did not pass legislation requiring any formal or standardized certification for teachers or professional development institutes. Instead, the Radical-dominated body focused on the requirement of oath tests for officers and teachers. In counties still controlled by Confederates, no school systems were created; therefore, no teachers or other local officers were employed and no oaths taken.

The hardline taken by Radicals in the legislature would have consequential results. Initially, ex-Confederates were disenfranchised. As in other states, Republican dominated legislatures did not feel that ex-Confederates could be “entrusted with political power” until they had proven themselves worthy to be rehabilitated back into the body politic. In 1866, an amendment was made to the state constitution which disenfranchised between 10,000-20,000 ex-Confederates. In 1870, an amendment to repeal the disenfranchisement was proposed and passed by referendum in 1871. While this overture was made by progressive Republicans to make amends for the 1866 amendment, it backfired, opening a channel for those disenfranchised to seek retribution. In 1870, Democrats had gained control of both the legislature and the governorship. By February of 1871 they called for a bill of convention.

Bibliography

Ambler, Charles H. A History of Education in West Virginia: From Early Colonial Times to 1949. Huntington: Standard Printing & Publishing Company. 1951.

Callahan, James Morton. Semi-Centennial History of West Virginia. Semi-Centennial Commission of West Virginia. Charleston, WV: Tribune Printing Co. Press. 1913.

Miller, Thomas C. “The History of Education in West Virginia,” Charleston: Tribune Printing Company, 1907.

“The Constitution of West Virginia, 1863. Article X.” West Virginia Archives and History. 2018. http://www.wvculture.org/history/statehood/constitution.html.

Whitehill, AR, “History of Education in West Virginia,” United States Bureau of Education Circular of Information No. 1, 1902. Washington: Government Printing Office.