Chapter 1: Education in colonial times

Chapter 2: Post-Revolution Education

Chapter 3: The Civil War and West Virginia Statehood

Chapter 4: Education System under the 1872 Constitution

Chapter 5: Era of Transformation, 1880-1909

Chapter 6 1909-1932: The Age of Uniformity & the Battle Between Old School and Progressive Education

Chapter 7 1933-1950: Education under the county unit, the Great Depression, WWII and Beyond

Chapter 1: Education in Colonial Times

In order to understand the development of education in West Virginia generally, and Wetzel County specifically, one must first look back to colonial times when the territory that would eventually become West Virginia was still part of the colony of Virginia. While the western territory of Virginia was veritably a wilderness even after America’s independence from Great Britain -- unsettled and without social institutions such as schools, courts, or magistrates -- the first school systems which did eventually develop were directly influenced by the educational systems developed in colonial times. Virginia, West Virginia’s “old Mother State,” was historically reluctant to institute a free public school system throughout its history.

There were two types of early schools in colonial Virginia. The first were led by private tutors, funded by plantation owners, to educate their own children. The private tutors were English and Scots who had been taught as “candidates for Orders” but who had not taken up religion as a profession. They had been well educated and often dedicated their lives to teaching. Virginia, like other southern states, lacked concentrated population centers, as those found in New England, in which village school systems could develop. As a result, schools were independent of government control. Often, tutors grew private employments on single plantations into private schools serving children from multiple plantations. These schools served wealthy planter children, children of overseers, craftsmen, and-- as population became more concentrated-- professionals like lawyers, merchants, and doctors. In exchange for full payment for services provided by overseers, craftsmen, etc., planters supplemented tuition for their children to attend schools on their plantations. Planters would also allow tutors to recruit from outside the plantation so as to supplement their income. When student population exceeded what the plantation’s building could contain, school houses were built.

In this way, private plantation tutoring evolved into common subscription schools. They commonly became known as Old Field Schools, without direct government or religious control. They were a product of the middle class as well as a budding capitalist system. Individuals funded the schools and chose the teachers. However, government and religious influence transpired. Certification of schoolmasters’ competency was first issued by the Church and later by the governor. Eventually county judges were granted authority to recommend schoolmasters for employment. This common school system, as it developed, would become the basis for the free public school system that began in 1863 in West Virginia.

In the first half of the eighteenth century, Old Field schools resided in the area which would become West Virginia . In 1747, the first known account of a school -- made by a surveying team that included George Washington -- appeared in what is now Hardy County, West Virginia. Washington’s August 18th journal entry referenced “the School House Old Field.” It can be reasonably assumed this was not the first common school in what would become West Virginia. But the state of wilderness in the region at the time resulted in a scarcity of records.

The first generation of settlers in the western region were “generally intelligent and literate” and understood the value of educating their children. Soon after Washington’s reference to a school, other references appeared of schools being established in western Virginia: schoolmaster Shrock was teaching in Romney, Hardy County, in 1753; a teacher was among those killed by Native Americans in the Greenbrier settlement in the same year; Thomas Opps was teaching in Brandywine, Pendleton County in 1758; and in 1762 there was an English and German school in what is now Shepherdstown. Each of these schools were located in the eastern panhandle, what would be known as the “Old Part of West Virginia.”

In the region from which Wetzel county would eventually break away, the earliest known account of a common school was in Ohio County (1787) just after the Revolutionary War. A teacher, Israel Donalson, taught there part time for three years. While this date might seem late relative to other accounts of teachers and old field schools in western Virginia, Donalson’s tenure as teacher was indeed within the first two decades of any permanent settlement in the region. Early exploration and settlement of this part of western Virginia began after the French and Indian War, and prior to the outbreak of war with Britain.

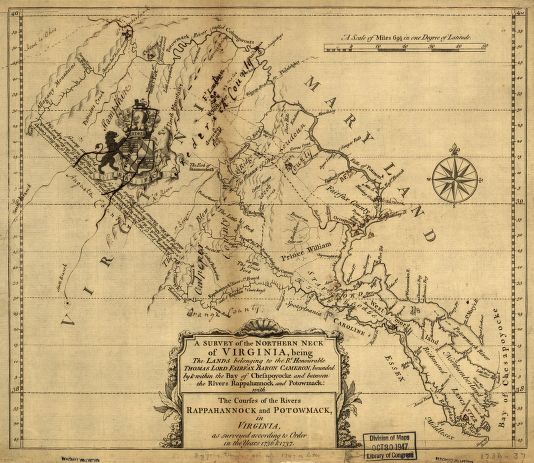

White settlement into the farthest reaches of western Virginia was facilitated by the Ohio River. Settlement westward from the eastern panhandle was slow due to the terrain of the Appalachian Mountains. To circumvent this geological barrier in moving westward, settlers began utilizing natural waterways to reach into the Ohio River valley. Again, George Washington plays a part in the story of the region. In 1770, he conducted a scouting mission -- down the Ohio River from Pittsburgh to the Kanawha River -- in order to survey land promised to soldiers who had fought in the French and Indian War. At this time, relations between whites and Native Americans were peaceful and this part of western Virginia had been completely untouched by white settlers.

In 1772, this began to change as whites began to make permanent settlements along the Ohio River near present day Wheeling and Moundsville (Grave Creek). By 1774, whites settling along the Ohio River led to rising tensions between Native Americans and settlers. Word reached the region that Indians were about to launch an attack. In 1774, in anticipation of attacks on settlers in Wheeling, Virginia, Fort Fincastle -- named after Lord Dunmore Royal Governor of Virginia -- was constructed . In 1776, the fort was renamed after Patrick Henry, the first governor of Virginia after the Declaration of Independence by the Second Continental Congress. That same year, Ohio County-- from which Wetzel would be partitioned-- was created from the District of West Augusta. It was in this county the first reported teacher, Israel Donalson, was to have taught in a common school.

The second type of schooling which developed in colonial Virginia, i.e. free public schools for indigent children, was religious in nature. The roots for charity schools can be traced back to English Poor Laws of 1601 which, in turn, established regulations for apprenticeship of poor and orphaned children. These were not paternalistic laws initiated to nurture or raise up indigent children. Rather, they were created to rid society of paupers, requiring children to earn their own keep, in a form of indentured servitude. By 1643, evidence of shifting sentiments arose in the role of guardians -- the General Assembly of colonial Virginia enjoined guardians of indigents or orphaned children to give basic religious instruction and education to their apprentices. By 1672, the local courts were endowed with the authority to oversee the apprenticeships and education of all indigent and orphaned children.

By 1705, masters were compelled to teach their wards religion and basic reading and writing. Church-wardens became central in the identification and placement of indigent children within the communities. By mid-century, it was required that indigent children be taught a trade as well as to read and write. And as the Revolutionary War approached, the obligation of the state -- in partnership with the church to provide education for the poor -- was part of the social fabric, so much so that the state’s obligation survived the separation of church and state established by the First Amendment of the US Constitution.

Bibliography

Ambler, Charles H. A History of Education in West Virginia: From Early Colonial Times to 1949. Huntington: Standard Printing & Publishing Company. 1951.

Cramner, Gibson L., ed. History of Wheeling City and Ohio County, West Virginia. Chicago: Biographical Publishing Company. 1902. https://www.wvgenweb.org/ohio/how-main.htm

Elvick, Neil. “Early History of the Upper Ohio River Valley.” Gallia History and Geneology. http://galliagenealogy.org/History/ohiovalleyhistory.htm.

McEldowney, John C. History of Wetzel County, West Virginia. 1901

Miller, Thomas C. “The History of Education in West Virginia,” Charleston: Tribune Printing Company, 1907.

Tomlinson, A.B. "First Settlement of Grave Creek” American Pioneer Vol. II, no. V (May 1843), pp. 347-57. http://www.wvculture.org/history/settlement/tomlinson.html