Chapter 1: Education in colonial times

Chapter 2: Post-Revolution Education

Chapter 3: The Civil War and West Virginia Statehood

Chapter 4: Education System under the 1872 Constitution

Chapter 5: Era of Transformation, 1880-1909

Chapter 6 1909-1932: The Age of Uniformity & the Battle Between Old School and Progressive Education

Chapter 7 1933-1950: Education under the county unit, the Great Depression, WWII and Beyond

Chapter 5: Era of Transformation 1880-1909: Graded and High Schools, Compulsory Attendance, Administrative Changes, Teacher Training Uniformity

The year 1880 marked the transitioning into a new era in the public school system in West Virginia. At the beginning of this new era West Virginia was far behind other states in the development of its public education system. Several reasons account for this. Up until this point, there had been legislative resistance to the public school system. But as legislators and superintendents from the antebellum era began to be replaced by those who had been educated in the public school system, much of that resistance turned to efforts of improvement and innovation. Charles Ambler attributes the underdevelopment to a “maladjustment to the Industrial Revolution.” The most talented persons of the period followed the money, which was in developing the state’s natural resources, not its children’s minds. Many corporations operating in the state were owned by out-of-state interests. This limited the amount of accessible resident capital. Additionally, the legislature incentivized outside investment through corporate tax breaks. All of these led to less available funds for educational investments. And where there was no industrial development, there was still only domestic economies and subsistence farming and therefore not much possibility for raising enough funds from local levies.

However, the next three decades would see statutory changes made to improve the public school system. Included in these, but not limited to, was the move towards a graded course of study and graduated system; a push to establish more high schools; compulsory attendance; administrative restructuring; and attempts in uniformity in teacher certification and training. This decade was the period in which the school system came of age and its administrative infrastructure was sufficiently intact to start making strides for statewide improvement.

Graded Course of Work and High Schools

By the early 1880s there were parts of the state which had effective school systems. Due in part to the industrial revolution and such tenants as Taylorism, many believed that education could and should be managed and funded scientifically. A major step forward in uniformity across the state was the graded course of study, or graduated system. It was first introduced in Monongalia County by Alex L. Wade in 1876. Wade’s plan believed that

adopting a course of study the free-school branches, organizing the more advanced pupils into four separate classes, according to their grades, fixing a time in which each pupil is expected to complete the course, holding annual examinations and commencement exercises in each district, granting diplomas to those who, upon examination, are found to be worthy of them….

would lead to more uniformity, progress and accountability throughout the state.

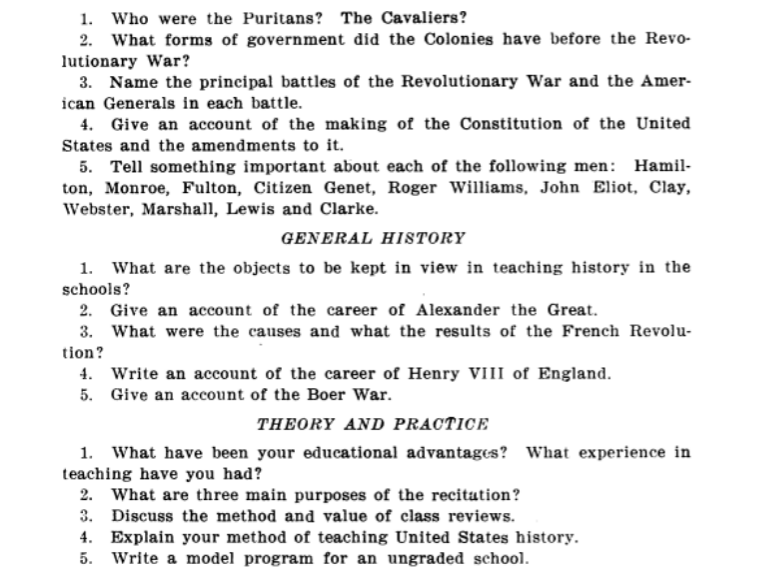

It was adopted countywide in 1881 and then statewide by legislative statute in 1891. The law required the State Superintendent of Free Schools to create and distribute a manual for a graded course of study in primary rural schools. The manual was required to outline courses to be studied and for how much time each should be given, provide benchmarks for students to advance from grade to grade, and criteria for graduation. The next year the legislature added more required courses to a total of the following: “bookkeeping, civil government, orthography, reading, penmanship, arithmetic, English grammar, United States history, general history, state history, physiology, hygiene.” Wade’s model was recognized and adopted nationally, even before it was implemented statewide. In 1894, Superintendent Virgil Lewis published “Manual and Graded Course of Study for Country and Village Schools” and by 1896 it was implemented nearly everywhere. Teachers generally accepted this system as a positive move forward.

The problem of establishing high schools during this time period was never fully addressed or fixed. The 1873 law allowed district boards to create high schools but only after it was approved by three-fifths of voters and subsequently reaffirmed in the 1881 and 1889 laws. In the 1880-81 school year, there were only 11 high schools in the entire state. In 1897 there were 25 statewide, in comparison to Pennsylvania and Ohio which had 256 and 474, respectively.

There were several reasons why high schools did not develop in the state during this time. First, many districts were unwilling to pay the special levy taxes required to fund high schools. Second, high school districts by nature needed to be larger than graded school districts because less students would be attending high school and many districts could not justify the cost for so few students. By high school age, many boys departed for the workforce, leaving girls as the majority of potential enrollees. One can not ignore gender bias as a deciding factor for the unwillingness to fund high school education.

Finally, most graduates of graded school moved on to Normal School for further instruction. Normal schools had been established to train teachers. These schools soon realized their students lacked the quality of education they would have received from high schools. As a result, adjustments were made to the curriculum to address these deficits. This adaptation affected the development of high schools.

But it was commonly felt among those in the education world that the development of high schools statewide was necessary for “the unification of the whole primary system” in each county because primary education’s curriculum-graded course of study was constructed in such a way to culminate in high school preparation. But this unification was never manifested. By the end of 1909 “the greatest educational need was still high schools.”

Compulsory Attendance

One factor which continued to delay education progress was poor pupil attendance. Because the 1872 Constitution required the provision of “a thorough and efficient system of free schools” it implicitly meant that the state could require compulsory attendance in order to ensure its thoroughness and efficiency. However, compulsory attendance flew in the face of many who believed in freedom of choice and disliked what they saw as government overreach. In the 1780s, it was common for only a third of eligible school-age children to attend school. For example, in the 1781 Biennial Report there were 166,749 enumerated children but the average daily attendance was only 51, 336, or 31%. The first attempt to remedy the attendance problem was made by the legislature in 1877. If school attendance fell below 35%, school trustees were required to close the school and dismiss the teacher. It was believed that this would cause social pressure on the teachers, trustees, and community in general to maintain attendance. But, with accountability falling solely on trustees and teachers (and not children or their parents) the law was ineffective.

The next attempt for attendance reform was pushed under the superintendency of Virgil Lewis who believed in compulsory education. By 1896, only 15% of eligible students enrolled in school and of those only 65% attended daily. The state had spent nearly $2.4 million on education and felt they were not getting the bang for their buck. Under pressure from Lewis, the legislature, in 1897, passed a new act which kept the 35% provision but required parents to send their child(ren) if they lived within two miles of a school. Parents would now be fined $2 if their child(ren) missed five consecutive days and $5 for every offence after the first. This law could be suspended if sixty percent of voters within the school subdistrict voted to nullify it. Also, there was no apparatus established for the payment of fines. Though this worked initially,parents soon discovered ways to get around the law.

Subsequent superintendents tried to reform the law. Under Superintendent Thomas Miller’s continued advocacy, the legislature mandated the establishment of truant officers to enforce the law in 1903. They also reduced the allowed missed days from five to two. In 1906, a drastic rise to 75% in average daily attendance resulted, but soon thereafter began to drop again. The school system was fighting bigger cultural issues, ones that statutes could not address through these punitive measures. Child labor was an issue, as well as apathy.

Changes with Administration- State and Local

During this era, state and local superintendents’ took on more important roles. The state superintendents, as mentioned earlier, were now from a new generation of men who came of age during and after the Civil War. They themselves were graduates of the free public school system. Consequently, they took the initiative to lead and promote educational innovations. Among the changes championed were compulsory attendance reform, standardized courses of study and teacher certification/training, expansion of high school education, and more accountability for local officials. While statutory law did not nominally change their duties, responsibilities, or powers, the superintendents changed the nature of their office by standardizing their roles in collecting data received from county superintendents, and then using that data to influence education legislation and inform their directives such as the graded course manuals.

County superintendents became more important during this same time. Before 1880, many called for the abolition of the county superintendent position, deeming the role as superfluous.. However, state superintendents realized they could utilize county superintendents as extensions of their own office to implement and improve at the local level. First, they entrusted local supers to monitor district finances within each county. Secondly, local supers could act as mentors for teachers, both tenured and new. During this time, high teacher turnover increased, finding better paying jobs in the private sector (e.g. competition from coal and oil companies in the development of the state’s natural resources). Also, through their leadership positions, superintendents could direct public opinion for educational improvement. By the 1890s, county superintendents were an essential part of the educational system and believed to be “the chief field officer of the Public School System,” thus making the elimination of their position impossible.

In a reversal of public opinion, calls were made to improve the position and expand their powers. By 1901, the legislature revamped the position. They tried to attract qualified and reputable people by issuing an improved salary schedule and extending terms to four years. But there were also restrictions-- they had to have previous teaching experience, could not teach while in the position, and had to make compulsory reports to the state superintendent.

Other local changes were made in statute as well. District boards still had authority over district levies, new construction and maintenance, and teacher salaries. But in an attempt to improve accountability the legislature allotted $1.50 per diem -- up to seven days a year -- for district board members to make their rounds to assess the state of education in their schools. The duties of the district boards included the following: establishing term lengths, salaries and employment of teachers, enumeration of students, building and maintaining schools, setting local levy rates, and general supervision. But during this time the power began to shift to trustees in order to combat board corruption. An 1881 act expanded the one member trusteeship to three. In 1889, 1891 and 1901 the legislature continued to expand the authority of trustees in making local decisions over teachers, as well as daily operations of schools.

Teacher Training Changes

Another area of change during this transition period was in teacher training and certification. Measurements of teachers’ competency were based upon mastery of content, and much less on methods or pedagogy. There were two main ways in which teachers were exposed to professional development. The first was through county and district teachers’ institutes, which were like extended normal school trainings. Instruction was based on a graded course of study which paralleled the graded courses implemented at the primary level at the same time. The effectiveness of these institutes varied throughout the state depending on the skill of institute presenters. Attendance to these institutes were annually compulsory, varying from one day to five through successive years. Even though the legislature required attendance to the institutes, it failed to fund them until the turn of the century. These institutes focused mainly on academics and assistance in passing teacher examinations. As time went on, elements of pedagogy were added. Unfortunately, this coincided with a decline in teacher institutes.

The second method used to ensure professional development was in the use of examinations to prove academic competency. The written exam dominated professional development at this time. From 1879 to 1887, all teacher certification went through county boards of education at will and was not standardized. There was a lot of corruption in the issuance of certificates. Teachers were given grades, 1-3, based upon the percentage of exam accuracy. Many complaints emerged about this system-- from local corruption to harshness of tests-- and people pressured the legislature to reform the system. In 1883, the legislature created a state board of examiners in an attempt to standardize the testing process, granting two grades of certification. Through the 1890s, the legislature continued to tweak this system but uniformity was not achieved.

In 1903, the legislature enacted a new uniform exam law. This called for exams to be held simultaneously throughout the state at specified times. To eliminate fraud and nepotism, exams were created and graded by the state superintendent . Three levels of certifications were issued, each determined by percentage scores. In 1904, a total of 3,812 teachers took the regularly scheduled exams. Of those, 682 received No. 1 certificates, 1,848 No. 2 certificates, 914 No. 3 certificates, and 368 failed the examination (See Appendix D). The failure rate for the previous year was a higher percentage. Many believed this new regimented system encouraged self-improvement and drove poor teachers out of the profession.

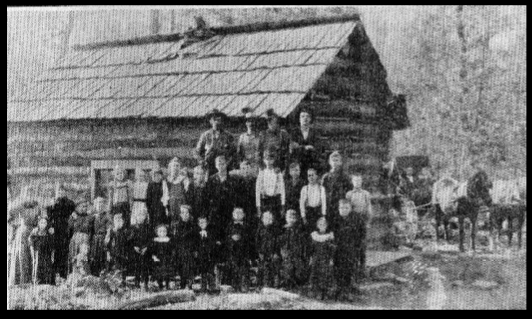

Overall, this transitory period in West Virginia’s education system brought uniformity wherein the previous decades were unable to create. Although the system had not been perfected it was moving in the right direction. By the end of the 1909 school year there were 93 high schools compared to 39 a decade earlier. (page 5) There were around 5,500 rural schools with more than 6,000 teachers. In 1880, Wetzel county did not chronicle the number of schools but reported “a lack of good schools in Grant and Green districts.” Many students traveled by foot four to five miles to get to the closest school and, subsequently, attendance was “far from good.” In Wetzel County alone, there were 151 schools by 1910. Attendance rates were improved and more qualified teachers were employed. Comparison of reports from the 1880s to 1910 shows improvement in the implementation of administrative apparatus and scientific management in school improvement.

Bibliography

Ambler, Charles H. A History of Education in West Virginia: From Early Colonial Times to 1949. Huntington: Standard Printing & Publishing Company. 1951.

Butcher, Bernard L., “ Biennial Report of the State Superintendent of Free Schools for the years 1881 to 1882,” Wheeling: W.J. Johnston, Public Printer. 1882. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015062795268;view=1up;seq=7 Accessed 3.29.19.

Lewis, C.S, “Eighth Annual Report of the General Superintendent of Public Schools,” Charleston:Henry S. Walker, Public Printer. 1872. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015062795441;view=1up;seq=12 Accessed 3.29.19.

Miller, Thomas C., “Biennial Report of the State Superintendent of Schools of the State of West Virginia for the Two Years Ending June 30, 1904,” Charleston: The Tribune Printing Company, 1905. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015062794733;view=1up;seq=9 accessed 3.30.19.

Miller, Thomas C. “The History of Education in West Virginia,” Charleston: Tribune Printing Company, 1907.

Pendleton, W.K., “Biennial Report of the State Superintendent of Free Schools of West Virginia for the years 1879 and 1880,” Wheeling: W.J. Johnston, public printer 1881. Page 86. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015062795425;view=1up;seq=7 accessed 3.30.19.

Shawkey, M.P., “Biennial Report of the State Superintendent of Free Schools of West Virginia for the two years ending June 30, 1910. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015062794717;view=1up;seq=9 accessed 3.30.19.

Whitehill, AR, “History of Education in West Virginia,” United States Bureau of Education Circular of Information No. 1, 1902. Washington: Government Printing Office.