Chapter 1: Education in colonial times

Chapter 2: Post-Revolution Education

Chapter 3: The Civil War and West Virginia Statehood

Chapter 4: Education System under the 1872 Constitution

Chapter 5: Era of Transformation, 1880-1909

Chapter 6 1909-1932: The Age of Uniformity & the Battle Between Old School and Progressive Education

Chapter 7 1933-1950: Education under the county unit, the Great Depression, WWII and Beyond

Development of Wetzel County Schools

Chapter 8: Analysis of the development of Wetzel County Schools through documents

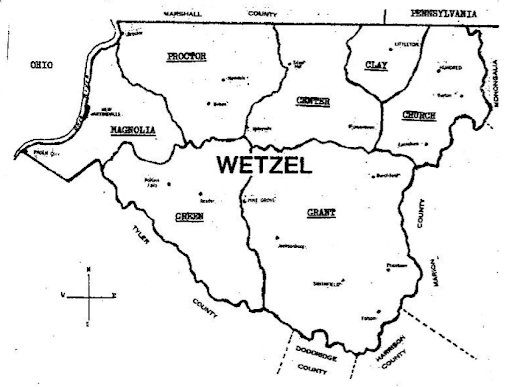

The formation of Wetzel County as its own political entity was discussed in Chapter 2. The division from Tyler County was a natural development. The geography of the land of Wetzel County was distinct from its border counties. Understanding these differences are crucial to grasping the development of the public schools system in the county. Additionally, had it not been for the rich natural resources buried beneath the county, the schools would have developed much differently. The correlation of geography and mineral development to the nature of the school system are inseparable. This chapter will explain how place influenced the people who lived here, and specifically, how they were educated.

How geography influenced development of schools

Research discovered over one hundred and forty schools located throughout the county over the period beginning in the 1850s to the mid 1940s. It should be noted that there were undoubtedly several more of which their existence has been lost to posterity. In the early days of settlement, the chaos of civil war, and the rush to construct new institutions during the early statehood period, led to many lost , or worse, simply unrecorded records. Even records during the time of relative uniformity (early 1900s to 1932) were lost as the county transitioned from seven separate school districts to the county unit system of 1933. But why was it necessary to have so many schools (an average of a school every 2.5 miles) in such a relatively small area?

In 1850, the population density of Wetzel was less than twelve people per square mile (refer to Appendix N). By contrast, its mother county, Tyler, had a population density of nearly double that in the same census (at 265 square miles and a population of 5,498). What prevented people from settling in this area?

Wetzel County is part of the geographic feature known as the Appalachian Plateau. Its land is characterized by precipitous hillsides, very narrow V-shaped valleys with very little flat floodplain acreage. The ridges are narrow, not rolling. The only sizeable flood plains with low slope exist along the Ohio River on the county’s most western boundaries. Only 1.6% of the acreage of Wetzel County is considered suitable for farmland. Seventy-five percent of all acreage is on a 25-75 percent slope. These geographic statistics give testimony to the difficulty settlers had in rendering an existence in the area, thus the sparsity of population.

In contrast, the surrounding counties were significantly more conducive to human settlement. To the south, Tyler and Pleasants counties had less than half of their acreage at a 35-75% slope. Marshall County to the north holds approximately 54% of its land at a 30-55% slope. Marion and Monongalia counties to the east have a combined 42.5% of their land at a 25-65% slope. The surrounding counties were more geographically hospitable to human settlement.

From the county’s inception to the late 1800s, geography explains why so few schools developed in the area. The first reported schools were found along the Ohio River flood plain where the lay of the land was more conducive to human settlement. The first school was in a farmhouse owned by the Williams’ family (located on Williams’ Run across the road from the current Bob Evans location). Later, a school house called Gravel Point Academy was erected near the Williams’ house.

Another school was purportedly operated out of a building in the backyard of the McCaskey family home, proximate to the current Peoples Bank on Main Street. Another school was at a carding factory at the junction of Martin and Jefferson Avenues. But likely the earliest two schools (after the Williams’ school) were the New Martinsville Academy (1854) and Gravel Bottom Academy in Steelton (early 1850s). As far as remaining records stand, New Martinsville is where education began in Wetzel County. This is plausible because it was one of the few areas which could sustain larger concentrations of populations due to its geographic floodplain features.

Comparing Wetzel County with the rest of western Virginia (Chapter 2: Post-Revolution), school systems developed in the same way, initially in population centers springing up along flood plains , by riverways, i.e. transportation routes. Wetzel did not develop independent school systems like those in Wheeling (an Ohio River town) or Charleston (a Kanawha River town) in large part because of low population density. But like other western Virginian counties, Wetzel’s earliest schoolhouses were subscription schools, as Virginia had no effective publicly funded system. The Civil War and statehood (Chapter 3), however, would change this by creating a legal system which could facilitate the establishment of public schools.

After statehood, the development of Wetzel’s public school system was slow. The first annual report issued shows Wetzel County as making some progress. By 1871, there were 61 schools in the county servicing 2,677 students, taught by 72 teachers. However, attendance was poor. Nine new schoolhouses had been built that year and a few more were under contract. Teachers were not indigenous (from Ohio or Pennsylvania) as training facilities in the state were protean at best. As mentioned in Chapter 3, the legislature was less concerned about teacher qualifications and more about requiring loyalty oaths to weed out ex-confederates. However, Wetzel County superintendent, William A. Newman, in order to improve the overall system, took the initiative to locally improve teachers-training and school finances .

By 1872, the state had a new constitution guaranteeing a free public school system. While the state was being taken over by Democrats sympathetic to the old Confederate cause (reestablishing rights to those disenfranchised by the 1863 constitution) it did not concentrate efforts on bringing uniformity from the state level to the local level. The counties and their separate district boards had no state guidance.

But the legislature had put into place statutory apparatuses which the counties could use to improve their systems internally. The first was with funding, which was dependent upon local levies-- fifty cents for every $100 of assessed property. This led to disparities among county districts, i.e. those having higher valued property had higher levy revenues. The legislature also passed a laws to help improve teacher quality, establishing a three person certification board, three levels of certification, the creation of more Normal Schools, and mandated district institutes for teacher training. This gave local authority initiative power to attempt uniformity and growth.

Wetzel County utilized the tools bestowed upon it by the legislature to improve its school system. In 1873, Superintendent Newman reported that much of the resistance to free public schools was dying. He reported six districts with seventy two schools -- up eleven schools from 1871. The graded certificate law had been implemented -- 22 teachers held grade 1 certificates, 28 held grade 2, thirteen held grade 3, and only 8 held grade 4. By 1874, Newman reported eight more schools, bringing the total to 78. While he did not mention district institutes, he did state that several more teachers -- though not enough -- had been trained at Normal Schools. He was optimistic as to where the county was headed. But, this growth was not consistent and continued in starts and stops. By 1878, Wetzel County had only grown to 80 common schools. The momentum of Newman’s 1874 report had stalled. In short, Wetzel County’s development from 1872 to 1880 was much like that of the state’s -- it was slow going with attempts at uniformity. But this protean system had laid the groundwork for the next era, 1880-1909: the Era of Transformation.

The Era of Transformation was characterized by the implementation of graded course work, creation of a secondary education system, and more uniformity in teacher training and certification. This era laid the foundations for a modern education system. Coexisting at the same time were old log cabin schoolhouses and brick buildings with modern furnishings. Wetzel county witnesses the transformation, albeit inconsistently.

In 1880, the number of schools remained the same as in 1878 (with 94 teachers), but one building had become a high school. This high school was located in New Martinsville, Magnolia district. It was authorized by the people of the district, subdistrict number 5, with only three dissenting votes. This was only made possible by years of efforts by townspeople. The board had been dominated by people who lived outside subdistrict 5 (New Martinsville) instigating citizens of the town to campaign for elected residents to the board.

By the August 1879 election, citizens elected enough members to vote in favor of allocating funds for a high school. By a 3-2 vote, Magnolia Board of Education not only voted for a high school, but also a special levy to raise funds, and purchase land. In 1880, the construction of a modern brick school was underway. The organization of the school and its coursework took shape over the 1880s. Eventually, the district came around to the idea and supported Magnolia High School. The first official graduating class with a commencement was not until 1893.

Unfortunately, it would be years before the high school ideal would gain traction throughout the entire county. The next attempt occurred in Clay District (Littleton High School) built in 1907. This brick structure contained both the elementary school and high school and offered a two year course of study. Not until steps were taken at the state level -- with the creation of a Division of High Schools in the Board of Education, and the appointment of a State Superintendent of High Schools in 1909 -- would Wetzel County have a strong high school movement.

The move towards higher education also coincided with the transitioning to more modern school structures. As mentioned previously, Magnolia and and Littleton High schools were brick structures. Records from 1881-82 show a growth of eleven more schools--66 frame, 2 brick, and 23 log. All this with still only 94 teachers. Slowly log schoolhouses would disappear, replaced by frame and brick structures. The last log cabin schoolhouse was destroyed by fire in 1898 or 1899.

Additionally, during this time Wetzel county introduced the first graded schools. This new system was met with resistance. By the end of 1884 there were 102 schools with 106 teachers. The two year report ending in 1886 by superintendent Haskins listed school totals at 104, with two having adopted the graded method. Two years later in 1888 there were 118 teachers, four graded and 104 common schools, totalling 108. In 1890, the county had 121 teachers, one high school and 112 common schools, totalling 113.

By this point, the county reported no graded schools. All were now common schools. This reversion is testament to the reluctance of teachers to implement the new program. But, to put it in perspective, Alexander Wade had just created the system in 1876; it had only been adopted county-wide in Monongalia (a neighbor of Wetzel) in 1881; and the state would not mandate its implementation through statute until 1891, giving a few years’ grace period for compliance. In this perspective, Wetzel was on the cutting edge of attempting to implement both curricular and grade uniformity, although this first attempt was not successful.

Another transformation taking place during this era was an attempted standardization in teaching certification and training. Improving the quality of teachers employed was priority. In the previous era, the legislature had authorized Normal Schools and district institutes for teacher training. Additionally, tedious examinations were administered at particular times throughout the state by appointed board overseers.

In 1892, Superintendent L.W. Delaney reported a “marked progress...among teachers” who were “energetic” and “wide-awake” to their profession. He discussed the “several district institutes” generated in Wetzel County throughout his tenure, stating “much good [had been] accomplished by and through district institutes.” The previous institute had educational experts -- from as far away as New York -- lead the seminars. Upon discussion of improving the rigor of examinations, he stated, the “better class of teachers [were] willing to work up to a standard of advancement.”

The rigor of these exams increased, as did the desire of Wetzel County teachers to improve their performance on them. By 1902 the Uniform System of Examinations was in place. The difficulty of this test was met by determined Wetzel teachers who worked hard to pass it. In 1903, only nine teachers were awarded No. 1 certificates; 25 got No. 2 certificates; 28 No. 3 certificates; and 25 completely failed. However the next year, 19 achieved No. 1 certificates; 41 and 17 received No. 2 and No. 3 certificates, respectively; and failure rates went down to only nine (Refer to Appendix D). By 1908, less than 13% of Wetzel teachers who attempted the test failed it.

The improvement of teacher certification, implementation of graded course work, building of modern schools, and introduction of secondary education each helped in the expansion of schools in Wetzel County. In a matter of twenty years, the number of schools had doubled in the county while the population had only risen by 51% (refer to Appendix N). Population growth alone cannot account for this dramatic growth in schools. Nor can a shift in cultural attitudes toward education. Schools are increasingly expensive to operate, leaving only an increase in the material wealth of this area to explain this development. It should be noted, at this time the financial responsibility for funding public schools lay on the willingness of the magisterial districts to raise levies, and not the state.

What, then, caused the massive development in schools? The discovery of rich mineral wealth under Wetzel County led to an economic boom starting in the 1880s, persisting until its decline in the 20th century. The first oil and gas was discovered in the Smithfield area in the 1880s. By the 1890s, every district -- except that of Magnolia -- was rich with “liquid gold” . The 1896 Stringtown oilfield, on the border area between Wetzel and Tyler counties, was developed. Boom towns popped up, including Piney Fork, King, Ross, Buffalo Run, Buck Run, Folsom, and Archers (Arches). Schools sprung up in all of these areas.

Wetzel County was West Virginia’s richest county with regard to oil and gas reserves. Additionally, the eastern two-thirds (mostly in Grant district) sat above the Pittsburg [sic] coal seam. The abundance of mineral wealth led to the sharp rise in boom towns, increased population, and higher assessed property value. This, in turn, led to the construction of more public schools as levy values went up.

According to a 1909 report, there were 310 numbered gas wells. Grant district contained the most at 110. Church district came in second with 52 wells. Center had 48 wells while Green district was right behind with 44 wells. Proctor district had 27 wells. And Clay and Magnolia districts brought up the end with sixteen and thirteen wells respectively. Because of the richness of natural gas, Wetzel had, at the time, produced more than any other county in the state.

Industries relating to the oil and gas boom followed. In Hastings -- a Grant district company town -- the largest natural gas pumping station in the world was constructed by Hope Natural Gas Company. Steel and glass factories, powered by natural gas, sprang up in Magnolia district in both New Martinsville and Paden City.

Because of the oil and gas boom, transportation also improved. While the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad was completed in 1852, it only narrowly traced through Wetzel county via the northeastern most part of the county. While affecting the population in that sector, the rest of the county was unaffected. The Short Line Railroad (completed in 1902), however, cut through three magisterial districts and opened some of the most rural districts to commerce and greater mobility. Railroads transported not only oil and gas, but people as well.

The economic boom from the oil and gas development led to increased population and increased tax revenue. During this period Wetzel’s population grew from 16,841 to its peak of 23,855 (Refer to Appendix N). Because of this late economic boom Wetzel County’s real and personal property valuation was ranked fifth of all counties in the entire state at $31,056,828 ($847,671,927 in today’s money). The county was able to keep its levy rates low at fourteen and fifteen cents per $100 of valuation for buildings and teachers, respectively. Even with these low rates, the county was still able to generate sufficient funds to transform their school districts into a modern system. At the end of this era, the county had 144 frame school houses, and three brick. Total enumerated students were 7,884, 6,285 enrolled, andan average daily attendance of 3,885 (between 6 and 16 years of age). (See Appendix O)

The county continued to invest in teacher development. In 1908, the county hosted an instructor from Buffalo, NY to lead the session. A record amount of teachers attended, 165 in all. In short, the county was poised to move into a new era of education -- with better schools, teachers, and funds -- unlike it had ever experienced before. The possibilities seemed limitless at this point. But war, depression, and the collapse of the oil and gas industry would check all of these growth factors.

During the Age of Uniformity (see Chapter 6), Wetzel County paralleled the rest of the state in the expansion of high schools (both in construction and course work). But other aspects of its development were similar, such as further standardization and implementation of the graded system (see grade books from each district on website), introduction of more vocational coursework, shift from teacher examinations to pedagogical training (in both state and local normal schools, plus short-course institutes) and continued consolidation of rural schools. Also, changes in administrative positions helped bring uniformity to Wetzel schools.

As mentioned above, by the end of 1908 the county seemed poised for perpetual growth . Funds now available made the expansion of the school system, especially secondary schools, more realizable. In 1909, the state nudged the county along when the state superintendent created a division of high schools within the department of education, appointing a state supervisor of high schools to lead it. Part of this supervisor’s job was to help counties establish high schools. District supervisors were established to help rural school systems. The state also passed laws which created three classes of high schools-- 1st, 2nd, and 3rd classes-- ranked according to the number of years of coursework offered.

During this time a group of male educators were highly influential with moving the county forward in education, especially secondary education-- S.L. Long, B.G. Moore, D.L. Haught, John Shreve, F.M. Tuttle, J.H. Gorby, F.E. Morris, and Francis Shreve. S.L. Long served as county superintendent. B.G. Moore was the first district supervisor for rural schools. Prior to that he was Grant district superintendent, along with F.E. Morris, D.L. Haught (also superintendent in Church District) and F.M. Tuttle. John Shreve was granted principalship of Magnolia High School, and Gorby was that district’s superintendent.

One driving force behind the efforts of these men was a healthy competitive streak to be the best and outperform one another in their respective districts. F.M. Tuttle recounted in an interview such rivalry, stating that he, John and Francis Shreve, D.L. Haught, F.E. Morris each grew up together in Burchfield. Morris was the first to attain a Normal School--i.e. teacher training school-- in his district, i.e. Grant. Within two years, in order to establish their own Normal Schools, John Shreve, D.L. Haught and F.M. Tuttle each enrolled and completed course work at West Liberty Normal School . Such competition, holding onto childhood rivalries, led to more uniformity and better schools.

During this period eleven high schools emerged out of graded schools. Magnolia had established a high school decades previously. But Clay (first diplomas 1912), Grant (1909), Green (1914), Church (1923--students rode the train to Littleton prior to 1923), and Center (1924) districts each established high schools during this era. The drive to build new schools continued under the influence of strong-willed leaders. F.M. Tuttle said, “[I]n 1916 or 1917...we swung the election held for the purpose of implementing an extensive building program… New brick schools were built at Pine Grove, Smithfield, Jacksonburg, Folsom, Burchfield and Mobley.” The satisfaction of the work completed was palpable to the communities involved. “In all my years in school work I consider these my most enjoyable ones.”

In 1910, Wetzel had two high schools, twenty graded schools, 130 common schools, with a grand total of 151. The push for implementing the graded system was making headway, but still had a long way to go. Leaders in pedagogy, such as John Dewey and William Rainey Harper, engineered the philosophical change in graded work. The national and state Education Associations also pushed for standardization. The first manual for graded and high school work was issued by the state in 1910. By 1912, a revised issue was released. Throughout the 1920s, the department of education continued to revise and release updated manuals on graded work for primary school, and standard course work for the secondary levels (as mentioned in Chapter 6). Essentially, the graded system elevated the need for higher education since there was nowhere for students to go after the 8th graded year. Thus the push for junior high and senior high schools in the county.

Included in the revisions of high school course manuals was an increase in guidelines for vocational studies. The Smith-Hughes act of 1917 (as mentioned in Chapter 6) mandated vocational courses in high school. As the 1920s progressed, the high school course work manuals included more vocational work and less college preparatory classes. By 1926, due to the Smith-Hughes Act, Magnolia reported having robust industrial arts and home economics departments . Hundred High School, built in 1922 contained home economics rooms and manual training rooms for the vocational arts. Smithfield High School taught home economics and vocational courses as well in the 1920s. Undoubtedly, these were not the only schools teaching industrial and manual arts at the secondary level. Included in these course revisions, was the offering of night classes. In the early 1920s, Reader High School offered night classes to students who needed to work during the day. In order to not be charged with truancy, students who worked could attend these night classes. The state legislature passed statutes to accommodate rural students and alleviate labor shortages during the war.

Teacher training

During this time period changes took place in the methods by which teachers became certified. There was a shift away from reliance on examinations alone and towards certification through institutes -- the short course at normal schools, completion of the full course at normal schools, and through local normal schools.

Wetzel county had only one local normal school located in Pine Grove. It began as a fifth year of work at Pine Grove High school and was authorized by the state department of education due to a teacher shortage caused by WWI. Iva Myers was the first instructor. The courses offered included “Principles of Teaching, Psychology (Special Methods), Rural Sociology, School Management, Principles of Education, and Observation and Practice Teaching (36 weeks).”

Students who lived in other districts would board in Pine Grove while completing this fifth year. This was not cheap. From one young woman’s account her room and board cost $12.50 a week, equivalent to about $175 in today’s money. Not only that, those attending would often have to complete chores around the boarding house for further compensation and then travel home on the weekends to help with work on the farm. Many sacrifices were made by both students and families to gain this educational and career opportunity.

Consolidation

At the beginning of this era (1910), Wetzel County had 151 separate schools. In 1922, that number dropped to 130. The consolidation movement was underway, though confined to the elementary level. Between 1921-1922, the county closed three one-room school houses, added four high schools, maintained eleven schools with four or more rooms, built an additional three-room school (totalling two), and constructed four more two-room school houses. Children were being transported greater distances to attend larger schools. The 1931-1932 Educational Directory shows the number of one room schools had dropped to 93. That same year, the county maintained its eleven separate high schools, three of which were junior high, eight being senior high. For now, the high schools would be safe from consolidation. But changes would begin to take place at the end of the 1920s, and into the next era, that would lead to the closure of several community high schools.

The County Unit in Wetzel County, and Beyond.

Even prior to the Great Depression, Wetzel County had been slipping into an economic recession. The boom of the oil and gas industry was going bust, per the nature of economic bubbles when natural resources are discovered. Population peaked in the 1910 census and began declining by 1920, and steadily through the 1950s. While the county remained rich with oil and gas resources, the speculation bubble underwent correction. This correction preceded the great bottoming out of the economy which occurred by the end of the 1920s.

County unit

The revenue crisis created by the Great Depression led to changes in state law with respect to property assessments. In 1932, the legislature passed the tax limitation and classification of property amendment to assist those West Virginians unable to pay real and personal property tax obligations which had previously led to delinquencies and forfeitures of lands. This amendment created a devastating tax system impacting magisterial districts’ abilities to collect enough revenue to fund the school system. Unwillingness to repeal the tax amendment posited reorganization of the educational system as the sole means to fix the school revenue crisis (Refer to Chapter 7 for more detail about the tax amendment and its consequences).

The County Unit law of 1933 completely restructured the educational system of West Virginia. In Wetzel County, the law abolished the seven separate schools districts existing at the time. In its place, a single county board of education was created (with five members). This law helped distribute money more equitably through the county, it also reduced tax divisions, helped raise the status of the county superintendent as head administrator, put the whole county on a better financial footing (especially with more aid from the state) and helped standardized high schools under the six-year program (grades 7-12).

The positive financial aspects of both the tax limitation amendment and the county unit plan cannot be argued. First, those rural districts with low property assessments would now have access to the tax revenues from wealthier districts within the same county. It was a great leveling for educational opportunity. Also, the financial burden of funding schools shifted from local direct tax revenues to indirect state tax revenues. Prior to 1932-33, the state only shared five percent of the financial burden of funding school systems. After these changes, more of the school revenues issued from the state. (See Appendix Q).

Another side effect -- one many felt was a negative aspect of the County Unit law -- was the acceleration of consolidation. As the 1934 Biennial Report states, “consolidation of schools [was] easily accomplished. In Wetzel County, several schools were eliminated. Prior to 1933, Wetzel had eleven secondary schools. By 1945, four of those schools had been eliminated. In the first year of the county unit law’s implementation, eleven one-room, one two-room and one six-room schoolhouses were eliminated at the primary level. This did away with six teaching positions alone. Burchfield High School, Folsom Junior High, and Wileyville Junior High closed the first year under the county unit plan. By 1944, there were just 72 elementary schools left in Wetzel, down from 93 in 1932. Littleton High School closed in 1945 and students were bussed to Hundred High School. Considering this was the second high school established in the county, this closure must be met with some sadness. By the 1950-1951 school year, the number had dropped to 64 elementary schools and only six secondary schools.

The county would continue to consolidate its schools throughout the 1950s. It is believed the last one-room schoolhouse closed in 1958. The Spring of 1960 was the last commencement for Reader and Smithfield High Schools. Those schools were discontinued and students were bussed to the high school in Pine Grove, which had been renamed Valley High School.

Bibliography

“2010 Census Gazetteer Files,” United States Census Bureau, August 22, 2012. https://www2.census.gov/geo/docs/maps-data/data/gazetteer/counties_list_54.txt accessed 4.27.19

“Biennial Report of the State Superintendent of Free Schools of West Virginia in the year ending June 30 1910,” Charleston: https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015062794717;view=1up;seq=229 Accessed 4.30.19.

Butcher, Bernard. “Biennial Report of the State Superintendent of Free Public Schools of West Virginia for the Years 1881 and 1882” Wheeling: W J Johnston, Public Printer, 1882. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015062795268;view=1up;seq=33;size=125 Accessed 4.27.19

Butcher, Bernard. “Biennial Report of the State Superintendent of Free Public Schools of West Virginia for the Years 1883 and 1884” Wheeling: Charles S. Taney, State Printer. 1884. ,https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015062795417;view=1up;seq=188 Accessed 4.27.19

Byrne, BW. “Tenth and Eleventh Annual Reports of the General Superintendent of Public Schools of the State of WEst Virginia for the Years 1873 and 1874.” Charleston: John W. Gentry, Printer. 1875. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015062795284;view=1up;seq=7 . Accessed 4.27.19.

Chambers, Willis W. “West Virginia Educational Directory 1950-51” Charleston: Statistical Division of the Department of Education, pages 219-221.

Cooke, Jonathan W. “West Virginia Educational Directory for the School Year 1931-1932.” Charleston: Department of Education. Pages 26-27.

Dorsey, Brenda. “Wetzel County Oil Fields,” Wetzel County WVGenWeb, West Virginia Genealogy and History.The USGenWeb Project.2008 http://www.wvgenweb.org/wetzel/communities/Wetzel-Co-Oil-Fields.html accessed 4.27.19

Ford, George M. “Biennial Report of the State Superintendent of Free Schools of West Virginia in the year ending June 30, 1922.” Charleson: Tribune Printing Company. 1922. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015062698314;view=1up;seq=181 Accessed 4.30.19

Gilmore, Delbert, “History of Secondary Education in Wetzel County, West Virginia,” Morgantown: West Virginia University. 1945. West Virginia and Regional History Center

Hennen, Ray V. “West Virginia Geological Survey County Reports and Maps: Marshall, Wetzel and Tyler Counties.” Morgantown: Acme Publishing Company. 1909. page 45.

History of Wetzel County, West Virginia 1983. Wetzel County Genealogical Society. USA: Walsworth Printing Company. 1983.

Lewis, CS. “Eighth Annual Report of the General Superintendent of Public Schools of the State of West Virginia for the Year 1871,” Charleston: Henry S. Walker, Public Printer. 1872. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015062795441;view=1up;seq=7;size=125 accessed 4.27.19.

Miller, Thomas C. “Biennial Report of the State Superintendent of Schools of West Virginia for the Two Years Ending June 30, 1908.” Charleston: Tribune Printing Company. 1909. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015062794725;view=1up;seq=101 Accessed 4.30.19.

Morgan, Benjamin S. “Biennial Report of the State Superintendent of Free Public Schools of West Virginia for the Years 1885 and 1886” Charleston: Jason B. Taney, Public Printer. 1886. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015062795409;view=1up;seq=261;size=125 accessed 4.27.19.

Morgan, Benjamin S. “Biennial Report of the State Superintendent of Free Public Schools of West Virginia for the Years 1887 and 1888” Charleston: Moses W Donnally, Public Printer. 1888. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015062795250;view=1up;seq=7 . Accessed 4.27.19.

Morgan, Benjamin S. “Biennial Report of the State Superintendent of Free Public Schools of West Virginia for the Years 1889 and 1890” Charleston: Moses W Donnally, Public Printer. 1890.https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015062795243;view=1up;seq=176 Accessed 4.27.19.

Morgan, Benjamin S., “Biennial Report of the State Superintendent of Free Schools for the Years 1891 and 1892” Charleston: Moses W. Donnally, Public Printer. 1893. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015076589921;view=1up;seq=7 Accessed 4.29.19.

“National Historical GIS,” IPUMS NHGIS. https://www.nhgis.org/ accessed 4.27.19.

Pendleton, W. K. “Biennial Report of the State Superintendent of Free Public Schools of West Virginia for the Years 1877 and 1878” Wheeling: W J Johnston, Public Printer, 1878.https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015062795276;view=1up;seq=7 Accessed 4.29.19.

Pendleton, W. K. “Biennial Report of the State Superintendent of Free Public Schools of West Virginia for the Years 1879 and 1880” Wheeling: W J Johnston, Public Printer, 1881. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015062795425;view=1up;seq=7 Accessed 4.29.19

“Soil Survey of Marion and Monongalia Counties, West Virginia.” United States Department of Agriculture, Natural Resource Conservation Service. July 1982.

“Soil Survey of Marshall County, West Virginia” United States Department of Agriculture, Natural Resource Conservation Service. May 1960.

“Soil Survey of Pleasants and Tyler Counties, West Virginia,” United States Department of Agriculture, Natural Resource Conservation Service. July 1989.

“Soil Survey of Wetzel County, West Virginia” United States Department of Agriculture, Natural Resource Conservation Service. September 1995.

Trent W.W. “School Reorganization in West Virginia” Charleston: Department of Education, Statistical Division. 1938. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015076568388;view=1up;seq=28;size=75 Accessed 5.1.19.

Trent, W.W. “The Reorganization of Schools under the County Unit and Recommendations to the State Legislature of 1935: From the Biennial Report for the Two Years Ending June 30, 1934.” Charleston: Tribune Printing Company. 1934. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015076559650;view=1up;seq=30 Accessed 5.1.19.